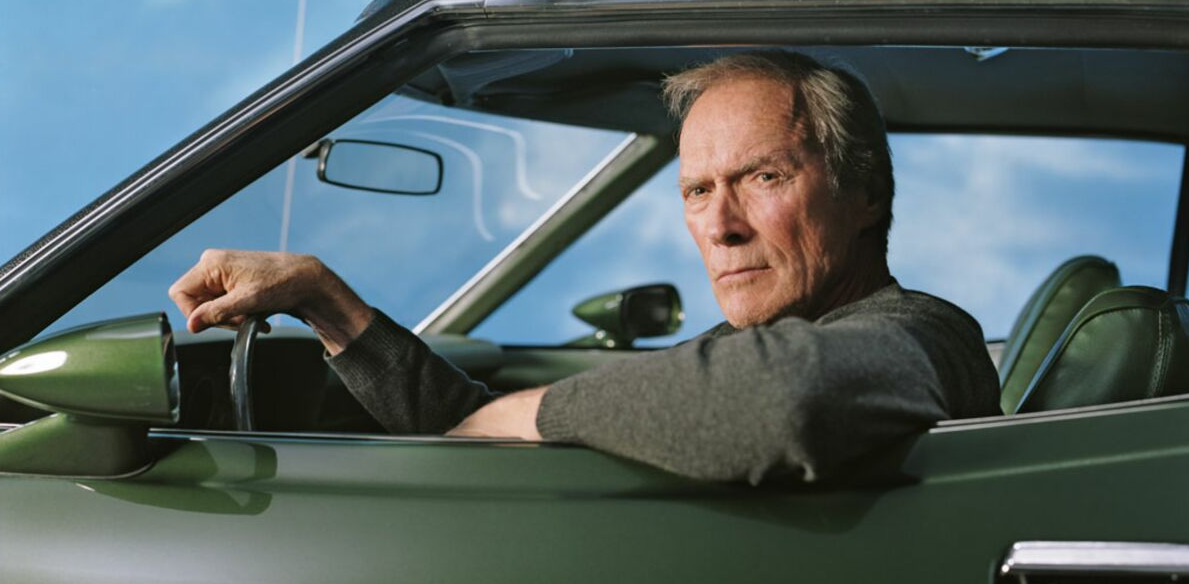

It’s hard to believe that Clint Eastwood turns 94 on the last day of May, but it’s not that long ago that he was playing a romantic lover in the film The Bridges of Madison County (1995).

Eastwood himself recently said that it is up to you to walk away when you still have the strength.

In action films the actor’s age is more noticeable; it is not for nothing that Leslie Nielsen, a popular Hollywood actor, quipped in a film parody that Clint, who played the US President’s bodyguard in In the Line of Fire (1993), was no longer as sprightly as he was when he chased after an armoured car.

It has already been announced that this year will see the premiere of Eastwood’s 46th directorial debut: Juror #2, a drama about an exemplary family man who, as a juror in a high-profile murder trial, is faced with a serious moral dilemma, the fate of a potentially innocent man.

Incidentally, Eastwood is the highest-grossing director for Warner Bros, one of Hollywood’s oldest film studios, and his own films have grossed more than three billion dollars.

Here’s a look back at Clint Eastwood’s top 10 film roles.

10. The Mule (2018)

In The Mule, Clint Eastwood’s protagonist is very similar to the character in Gran Torino – a former Korean War veteran, Walt Kowalski, who categorically refuses to live according to the rules of the modernizing world and who is indifferent to the political correctness that flourishes in America.

Equally sullen and silent is the loner Earl Stone, who belongs to the large legion of “losers”. Derisively referred to even by his ex-wife as ‘Mr. Botanist’, he has spent many years in a conservatory, growing rare varieties of orchids. But the business has collapsed, and the old man, who is in financial trouble, hopes to make amends by accepting a job as a driver in his old crockery truck, transporting small loads from A to B. It’s easy to see that such a small job pays big money for nothing.

We have certainly seen many stories like this in the cinema. We even have a Lithuanian documentary called Mules (that’s what drug couriers are called), made in 2018 by world traveler Martynas Starkus. It tells the story of three young people who ended up in Peruvian prisons for trying to smuggle drugs.

Clint Eastwood’s The Courier also tells a true story. The film’s script is based on a June 2014 article in The New York Times entitled “The Sinaloa Cartel’s 90-Year Old Drug Mule”.

P.S. Sinaloa is a state in western Mexico, on the Pacific coast.

The story described in this article was adapted into a screenplay by two Eastwood collaborators, Nick Schenk and Sam Dolnick.

The real “mule” was Leonard Sharp, a World War II veteran whose vegetable business collapsed, forcing the 80-year-old man to break the law. Police arrested him in 2011 with 90 kilos of drugs in the boot of his car. The consignment was worth around 3 million dollars.

The man pleaded not guilty in court and was sentenced to three years in prison. The court considered the defendant’s age, his past achievements, and the fact that the lawyers used a medical diagnosis of senile marasmus.

The main character in the film is called Earl Stone.

This story takes place in 2005. Still a sturdy old man, Earl Stone enjoys the pleasures of a dignified old age – he grows vegetables and flowers, often receives prizes at the annual florists’ convention, is convinced that the internet is a worthless invention, and doesn’t care about how his wife and daughter live.

But when a man loses his home to debt, there is an opportunity to make some easy money. All he has to do is take a parcel from one state to another. Then another, and another…

The success story of this rather long criminal odyssey is simple – the highway patrol certainly didn’t suspect a war veteran who drives an old crockpot and doesn’t break the rules of the road, and who is capable of transporting large quantities of contraband.

9. Gran Torino (2008)

Gran Torino is a well-preserved vintage 1972 car of which its owner, Walt Kowalski, is very proud. The gloomy silent man categorically refuses to live by the rules of the ever changing world. The former Korean War veteran is also indifferent to the political correctness that flourishes in America. If you call this old man a racist, he should not be angry. A recluse who has been kicked and thrown around by life, he trusts only two things: his always-ready weapon and his faithful dog, Daisy.

According to his son Mitch, Walt is stuck in the 1960s. He is a fossil in the eyes of his children, not to mention his grandchildren, who do not want to understand that the world has changed a lot since the Korean War. And Walt does not care. He is hurt that even the people closest to him have forgotten the good old American ideals. Sons are traitors, driving Japanese cars and engaging in “legal theft” – trading; granddaughters care about nothing but painted nails, belly button piercings and mobile phone chatter.

There is no respect for elders to speak of, if even in church, the milk-beetles mutter half-loudly, not the traditional words of prayer, but their own version of the “holy trinity”: “In the name of the internet, beer and sex”. Here, not being a saint, you’ll start to grumble with Walt: “Young people these days…”

The people Volt called neighbors are either dead or have moved elsewhere. In their stead immigrants from Asia came. Walt really hasn’t been fond of Asians since the war. As we see in the film, with good reason. The large Korean family living in the house next door makes no secret of their hostility towards their neighbor. Aggressive “narrow-eyed” wastrels drive around in luxury cars, brutally abusing decent passers-by. They accept only one argument – a strong fist or the barrel of a gun pointed at their face. Therefore, when Walt Kovalski, undaunted by the insolent attacks of thugs, slaps the scoundrels with his hands and feet, as Dirty Harry once did, it is not at all appropriate to call these acts violent.

The Hollywood veteran convinces us that there is no other way to fight violence on the dirty streets of big cities. All the talk about tolerance and humanity is just idle chatter.

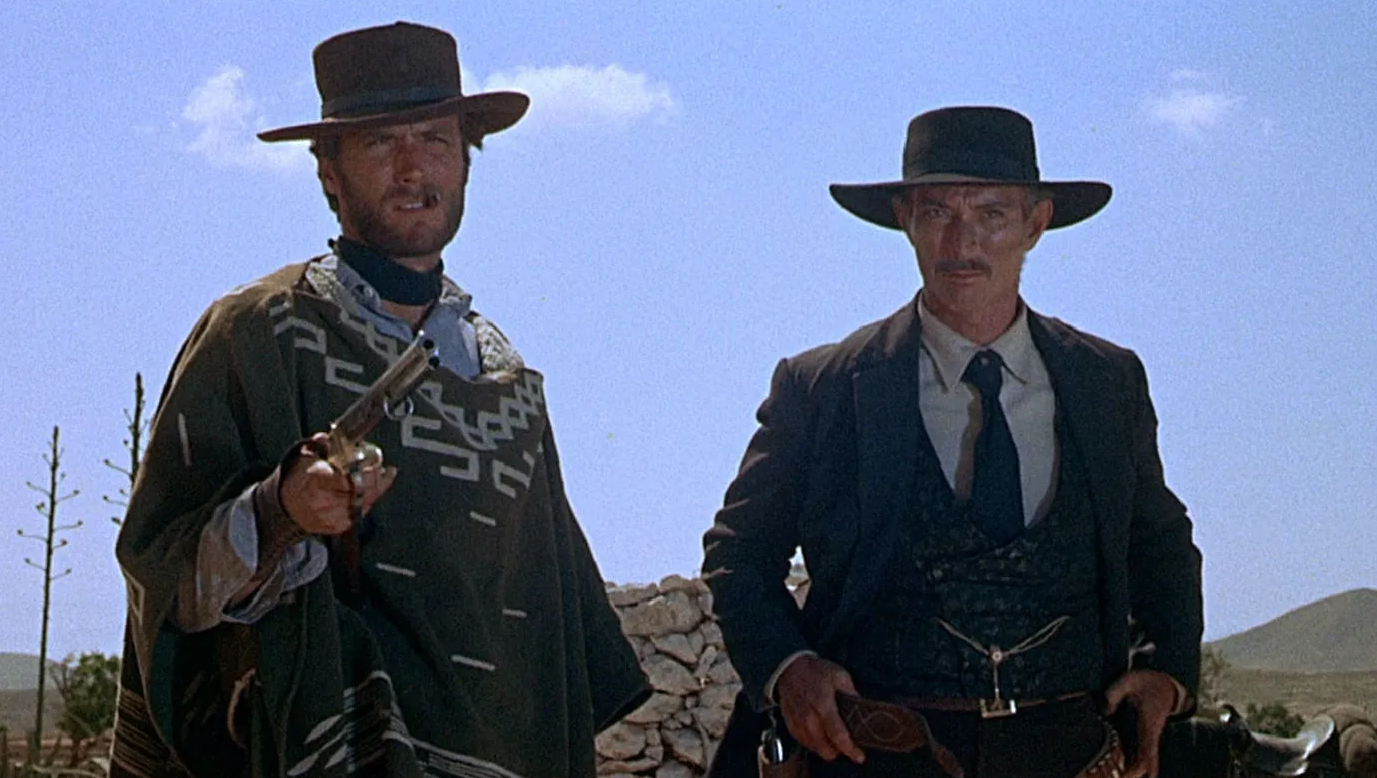

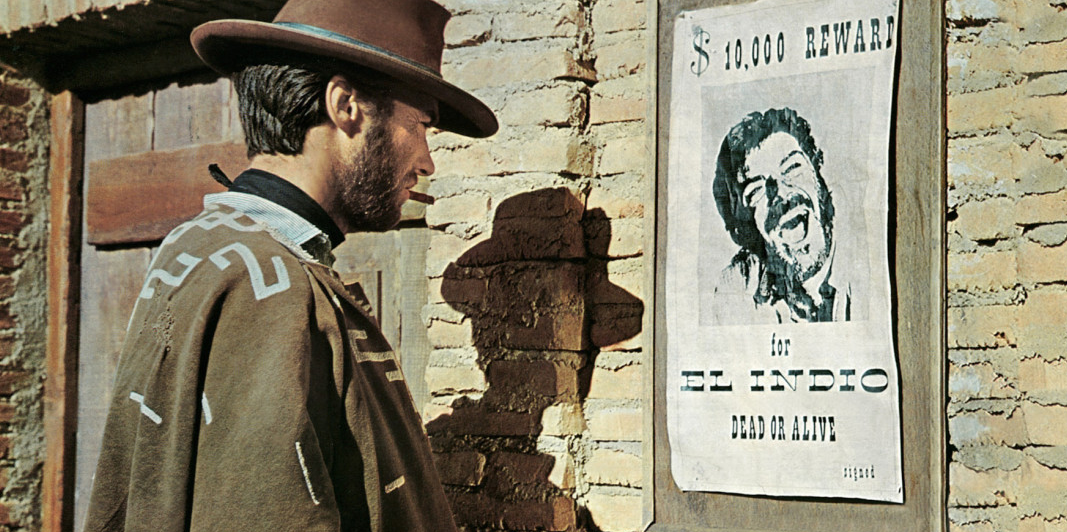

8. For a Few Dollars More (1965)

For A Few Dollars More is the second film in Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, starring Clint Eastwood as the protagonist and Gian Maria Volonte as his enemy. The film was first released in Italy in December 1965 and in the USA in 1967. The success of the first film led Leone and his producer Grimaldi to make a sequel. Although Charles Bronson refused to act in the second part, saying that the films were too similar, Eastwood liked the second part and agreed to continue acting. For this role, he received $500,000. In Italy, the film became the highest grossing film of all time. Later, a parody of the film, A Few Dollars Less (1966), was made.

Leon’s western film was budgeted at around $600,000 and it eventually grossed a hefty $15 million. The film was shot mainly in Spain and Rome. In Spain, the Almeria desert, where a special town was built for the film, is still operating. To this day it is open to tourists.

In this sequel, Colonel Douglas Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef) and Monk (Clint Eastwood) are searching for a bandit who is terrorizing the neighborhood, Indio (Gian Maria Volonte). Despite their uneasy relationship, the rivals’ common goal leads them to a truce, and they decide to join forces in order to catch the brutal bandit whether he’s dead or alive.

7. Million Dollar Baby (2004)

Clint Eastwood stars in this Oscar-winning drama, directed by himself, as Frankie Dunn, a professional coach who has spent his life training his charges to win at all costs. But before his fate, Frankie has long since lost his own duel. Now he can only rely on his old friend Scrap to help him maintain his modest boxing gym. One day, a girl called Maggie came in determined to become a professional boxer. For both Maggie and Frank, this is the perfect (if not the only) chance to redeem themselves.

In 2005, this film became a major contender at the Oscars. Even though it was edged out by Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator for the most statuettes, Million Dollar Baby was voted the best film of the year, winning the Oscars for Best Director, Best Actress in a Leading Role (Hilary Swank), and Best Supporting Actor (Morgan Freeman).

Some then rushed to call Million Dollar Baby the best boxing film of all time. This is, to say the least, not true. In sporting terminology, such a categorical statement is like a double banned punch. First of all, Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980) certainly did not take the best boxing film laurels from Million Dollar Baby. Secondly, this film is not about boxing at all. Though much of the film is set in the gym and in the ring, for the director and the lead actress, boxing is just a profession, a way of achieving a goal and a way of realizing something very important in life. The most interesting and valuable lessons are not learned in the ring. And they are not sports-related.

Rather, the director focuses on the themes of repentance, redemption and, in the words of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, “responsibility for those we tame”. Most sports-themed films are most impressed by the astonishing career milestones, fanatical dedication and determination that sooner or later will inevitably lead to the glittering pinnacles of triumph. Clint Eastwood takes a different path. He is still at the starting line thinking about the price he will have to pay for the intoxicating taste of success. After all, the saying goes, “The higher the rise, the harder the fall”.

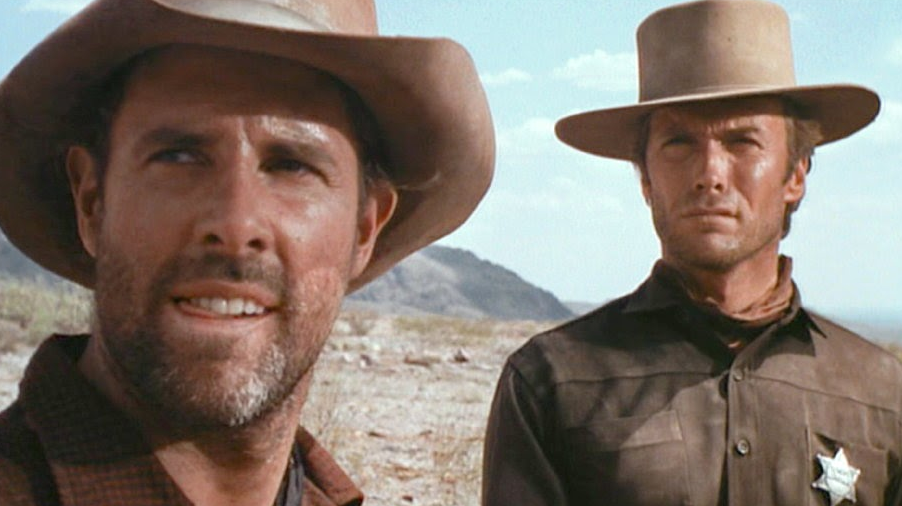

6. Hang ‘Em High (1968)

The film was released in America in 1968, just after Americans saw all three of Italian director Sergio Leone’s films: A Fistful of Dollars (1967), A Few Dollars More (1967) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1967), was when Eastwood became a global movie star.

Despite being made in America, Hang ‘Em High is strongly influenced by Italian spaghetti westerns. It was Ted Post, the director of this film, who was the first to develop it in the United States. Later, Don Siegel, a frequent partner of Eastwood’s, used the concept, and Eastwood himself, who became a director himself, developed it in his westerns on numerous occasions.

Hang ‘Em High is set in 1873 in Oklahoma. The outlaw hunter Jed Cooper (played by Eastwood) is accused of kidnapping a herd of cattle and killing its owner. Such a crime was then punishable by a lynching trial, and the furious farmers, led by Captain Wilson, are determined to do just that. But after a brutal execution, Jed survives and seeks revenge. He even becomes a marshal of justice.

This was the first film produced by Eastwood himself. By then he had already decided to move quickly into directing and even set up his own film company, Malpaso Productions.

Some of the characters in Hang ’em High had real-life prototypes, but with different names. For example, the town judge played by actor Pat Hingle is called Adam Fenton in the film, but the author was referring to the infamous Judge Isaac Parker, known as the Hanging Judge, who in the late 20th century, as a United States District Judge in Arkansas, often practiced the practice of hanging criminals.

5. A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

Back in the 1960s, a friend, actor David Janssen, helped Clint Eastwood get into the cinema, but for a long time Eastwood had to play insignificant series (often without even his name in the credits).

He would probably have remained an extra if it had not been for Italian director Sergio Leone, who came up with the idea of resuscitating the declining American western genre. He then invited Clint to play the lead role in A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

Several attempts have been made to rescue the traditional Western films from stereotypes and clichés, especially in the early 1970s, when the crisis of the genre began to worsen, and the Westerns became like sterile fairy tales. Then director Sam Peckinpah added fresh wine to the old wineskin, the films became rougher and more violent, and the Italian Sergio Leone, who has learnt these lessons, went even further by replacing good and bad characters with even worse and the worst ones, against which the protagonist seems relatively good guy (especially with the so-called spaghetti westerns).

This was also the case with Eastwood’s (anti)hero in A Fistful of Dollars. The actor said that he was thrown into the project by coincidence because James Coburn refused to do it for a small fee: “If the director had a bigger budget, he wouldn’t have even looked at me, he’d have hired James Stewart or Bob Mitchum.”

The screenplay was based on the story of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo 1961, but instead of medieval Japan it was set in the American Wild West. Filmed in Spain.

Eastwood plays the Man with No Name, who arrives in the bandit-infested town of San Miguel. Two gangs of bandits, the Baxters, backed by the local sheriff, and the Roca brothers, are in conflict. The newcomer offers his services to the leaders of both gangs and, by cleverly manipulating their interests, he significantly thins their ranks.

The film is full of violent scenes and crude, even “hilarious” humor, as the newcomer is greeted in the suburbs by a corpse with the words “Goodbye, amigo” written on his back.

Many of Leone’s inventions; long pauses, close-ups, striking shot compositions, unusual camera angles, contrasting scene changes, have also been used in other films. Ennio Morricone’s original music and, in particular, Eastwood’s character’s remarkable ability to remain impressively silent contributed to his success. The actor himself decided to do this, thinking it would be to his advantage. He was right for that. The psychiatrist Stanley Platman quickly confirmed Eastwood’s phenomenon: “The less we know about a person, the more we tend to believe that he is the person we want him to be.”

Challenging the traditional American Western was then a very risky and even audacious move. The director was aware of this and took the name Bob Robertson in the credits of the film, as did some of the other members of his team. However, it was unnecessary, as the unexpected revision of a classic western was very popular with the public, Leone soon made two more films, A Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1967).

4. Dirty Harry (1971)

After starring in three spaghetti westerns directed by Italian director S. Leone, Eastwood returned to his native America as a winner, and became a true star in his homeland in 1971, when he first played policeman Harry Callaghan in the crime thriller Dirty Harry.

His character was nicknamed for his determination and for not letting his revolver rust in its holster. Such strong arguments against brazen criminals did not go unanswered, and the actor later had to play Dirty Harry five more times. For this role, the French classic Jean-Luc Godard even called the actor a fascist, but later dedicated his film Detective (1985) to Eastwood.

Dirty Harry came to the attention of the US public for several reasons. The actor himself revealed one of them: “I’m not an advocate of violence, but we live in a world in which everyone has to deal with violence… You probably won’t find a person in America who is satisfied with our law enforcement.” The police were no longer respected. In San Francisco, where Dirty Harry is set, according to critic Pauline Kael, “even young children know about the corruption of the police, but there is not a word about it in the film. I myself grew up in San Francisco and have always remembered my mother’s words: “No matter what happens to you, never call the police”. I remember my teacher couldn’t understand why the worst of his students, the bullies and sadists, ended up not in jail but as policemen.”

The authors of Dirty Harry were of a similar opinion: corrupt cops will not defeat crime. Nor will overly liberal laws, which are far more favorable to lawbreakers than to knights of the law, help to tackle it. The only way out is to follow their own methods in the fight against criminals. This is what policeman Callaghan is successfully doing, in defiance of neither the law nor the ethics of the officer. In one scene in the film, after pushing a wounded bank robber to the ground and pointing a gun at him, he says: “I know what you’re thinking, you care how many shots I fired – five or six. I’ll tell you the truth, I didn’t count. But you know that the Magnum 44 is the most powerful gun in the world, and it can shatter your macula into pieces. You’d better think about whether this is your lucky day.” Harry pulls the trigger, and there is a dry rattle; there are no bullets left in the pistol’s clip. The thug trembles in fear, and the inspector smiles wryly.

Dirty Harry also provoked controversy because it was released at a time when American screens were being flooded with films depicting violence in a very realistic way.

The same can be said of contemporary crime films and TV series. And current action thrillers do not even show a minimum of sensitivity towards the audience. As a result, the escalation of violence has reached catastrophic levels. Nobody seems to know how to overcome it…

In Dirty Harry, Inspector Harry Callaghan investigates the case of a woman killed by a sniper. On the roof of a skyscraper, he finds a letter from the killer, in which the Scorpio gunman demands one hundred thousand dollars. Otherwise, he threatens to kill one person every day. While the city authorities ponder the situation, Harry takes action. His arguments against the rampaging criminals were so popular with audiences that four more Dirty Harry films were made.

3. The Bridges of Madison County (1995)

The Bridges of Madison County is a screen adaptation of the popular American book written by Robert James Waller. This is a not uncommon thing for Clint Eastwood; of the thirty-eight films he has directed, most are based on original screenplays.

In the gallery of films based on books (apart from The Bridges of Madison County), we can see Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997), Absolute Power (1997), True Crime (1999), Blood Work (2002) and Mystic River (2003). The drama about Nelson Mandela, Invictus (2009), was also adapted from the book. American Sniper (2014) and Sully (2016) round off the list.

At the beginning of the emotional melodrama (a rare genre in Clint Eastwood’s oeuvre) The Bridges of Madison County, Carolyn Johnson (Annie Corley) and her brother Michael (Victor Slezak) discover the diary of the late Francesca (Meryl Streep) after the death of their mother. It describes a love story, carefully hidden from her family, that happened to her with a wandering photographer, Robert Kincaid. He was in Madison County photographing the town’s famous bridges for National Geographic. When he got lost, he wandered onto a lonely farm…

As a young woman, Francesca fell in love with an American and left her native Italy for America with her lover. The lovers settled on a farm in Iowa, raised their children, and seemed to wish for nothing. But Francesca’s serenity was suddenly shattered by a chance encounter with a kindred spirit. Overwhelmed by her new feelings, she is faced with the daunting task of succumbing to the impulses of her feelings and leaving with Robert for the wide world or staying on the farm until the end of her days.

Writer Robert James Waller said he wrote his book in ten days. He did not expect much success, so he made several copies of the manuscript and gave them to family members and close friends. One of his friends knew a Hollywood literary agent who became interested in the possibility of a screen adaptation. But finding the right director and the right actors proved to be a challenge. The project only got off the ground when directors Sydney Pollack and Bruce Beresford dropped out and were replaced by Clint Eastwood.

The list of actresses who turned down the role of Francesca is much longer: Susan Sarandon, Jessica Lange, Barbara Hershey, Anjelica Huston, even the singer Cher was consulted, as well as two European actresses – Isabella Rossellini and Catherine Deneuve. In the end, Meryl Streep was accepted, which was the best solution.

The film was a real success, as evidenced by the countless positive reviews and the excellent financial figures (budget: USD 24 million, worldwide income: 183 million).

2. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Clint Eastwood gave one of his most memorable performances in this epic 1966 Sergio Leone western, which centers on a race to unearth a golden treasure buried in a village cemetery, illustrating the beginnings of a difficult collaboration between the three men before the fourth. The final part of the Dollars Trilogy, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, is probably the most famous spaghetti western in the world. The latter, somewhat comical-sounding title has stuck to American-style westerns made by Italian directors. They are characterized by a somber mood, multiple pauses, large sets and choreographed scenes of violence.

Set during the Civil War, the story tells the story of three protagonists: the mysterious, soft-spoken newcomer “The Good”, the cold-blooded bounty hunter “The Bad”, and the shrewd, but not particularly intelligent Mexican bandit “The Ugly”. The trio race to find gold buried in an unmarked grave at any cost. In fact, the three protagonists are neither better nor worse than each other. In the desperate search for gold, even the “Good” character repeatedly breaks both the law and morality. From the actors’ roles and memorable lines to the characters’ clothing and the soundtrack, it’s hard to find a detail that hasn’t already been used as an inspiration for further westerns. Widely acknowledged as one of the best not only among westerns but also among films in general, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly deserves attention in every scene.

The cast of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is distinguished by its unforgettable narrative and its superb cast.

1. Unforgiven (1992)

Westerns occupy a large and important place in Clint Eastwood’s work. Not even the traditional, American ones, but the Italian ones (hence dubbed spaghetti westerns by film critics in the 1960s). It was Clint Eastwood’s role in A Fistful of Dollars in 1964 that made him a movie star.

This and Sergio Leone’s Italian Westerns A Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) influenced the western and changed the rules of the genre that even Americans themselves (e.g. The American filmmakers, Don Siegel, and Clint Eastwood, who started directing, have made several Westerns in the same fashion: the High Plains Drifter (1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) and Pale Rider (1985).

Clint Eastwood dedicated his last western, Unforgiven (1992), to his friends Sergio Leone and Don Siegel. This film won a significant number of Oscars (four for Best Film of the Year, for directing, editing and a supporting role for Gene Hackman), but it was also named the best western of the decade – the pinnacle of the modern western – cold and unattainable.

On these heights, the collapse of all beautiful illusions awaits us. They have long since been buried with his dead wife by the ageing cowboy William Munny (played to perfection by Clint Eastwood), who now soothes his heartache with whiskey and wallows in the dirt of his farm and the dung of his pigs. Life forces him to take up arms again and, together with his two sidekicks, take on the role of judge. Not so much for justice (someone has to avenge the defilement of a prostitute), as for money.

It all started in 1881, when Munny, who lives on a farm with his son and daughter, is visited by a young gunslinger, Schofield (Jaimz Woolvett), who offers him a thousand-dollar reward for killing two bad guys who have carved the face of a brothel prostitute with a knife. The money is collected by poor Delilah co-workers, but Schofield doesn’t trust himself alone, so he finds Munny.

Munny used to be a great headhunter, but now his eyes are not so sharp, and his hands shake treacherously. But Munny has nothing to lose, so he agrees after some hesitation. On one condition – Munny’s old friend Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) must come along.

When the film was released, the French film magazine Studio declared: “We must face up to what is already clear: Clint Eastwood’s new film, Unforgiven, is the last western in the history of cinema. It is the last chapter, the epilogue of the genre”.

The magazine goes on to say, “Eastwood had the script as early as 1982, but waited until he was 62, the age of his character. He was right to do so. The script could not age; it is timeless. Western is a genre that is always flirting with mythology. The screenwriter, David Peoples, was well aware of this, but he was trying to reach depths that had not been explored before.

The film doesn’t play with mythology, it is in the depths of it. In the impenetrable darkness. Where no God has any power anymore and where man is forever damned. And that is worse than hell.”