Any work of art will, inevitably, place itself squarely on the great divide between the artist’s actual intents, influences and thoughts and what the audience perceives these to be like. The subjectivity of art stems from this divide.

Some look at the Mona Lisa, for instance, and see a woman smiling. Some see a centuries-long conspiracy. Some don’t get what the fuss is about. Neither of these viewpoints are falsifiable, simply because they are opinions based around an object left open to interpretation.

It is precisely this reason (openness to different viewpoints) is that counter-cultures, no matter what they are or what they contain, tend to devolve into sub-cultures over time. The process, outlined in numerous sources, is simple: the movement is pioneered by individuals who have an as-of-then “different” manner of doing things. It could be working-class frustration let out on stage over three-chord songs like punk, or seeking a more melancholy aesthetic like Goth Likeminded individuals will inevitably meet, exchange notes, push the envelope of what they perceive to be their own context.

It is at this point, where the pioneers inevitably garner attention that they push the first domino. As the amount of people subscribing to what is displayed, in one way or another, the context itself starts to become distinctive. Traits common to those existing within the counter-culture begin to emerge, and begin to spread. Individuality is downgraded to individuality-in-context, identity begins to define groups instead of singular entities, quirks and deviations become norms and standards. What once was strange and unusual thus becomes familiar and, more importantly, adoptable. Adoptability breeds accessibility, and where something is accessible, a market for it grows, sealing the fate of what once was an outlier by forcibly dragging it into the standard distribution.

The existence of so many clothing brands belonging to the counter-culture to end all counter-cultures, punk, is a testament to how much of a gross subversion this last step becomes: for a movement that was based fundamentally on a DIY (Do-It-Yourself) mindset, a clothing line is the exact opposite of what it is supposedly based on. We might turn to the 1979 Bauhaus single, “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.” Now, it is considered to be an anthem of gothic subculture. What is lesser known, however, is that Bauhaus wrote the song to poke fun at the “gothic” crowd that appeared to not only subscribe to the supposed “requirements” of the subculture, but almost enforced it as well. A song meant to be satirical was understood as descriptive, which is basically how the process works.

At this point, I would like to turn to a more popular example to demonstrate how audience perceptions can often run counter to the artist’s intent. None more poignant in this regard than the work of the iconoclastic Jhonen Vasquez.

Johnny the Homicidal Maniac

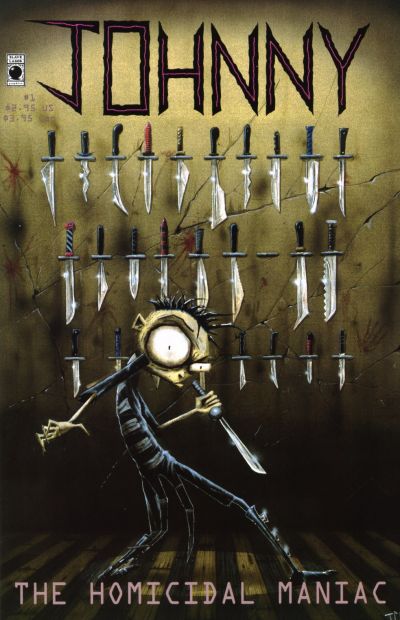

His second most famous work, Johnny the Homicidal Maniac (henceforth JtHM) was a limited series comic, published initially as single issues (seven in total) between 1995 and 1997. It was, at the time, a unique body of work. Featuring a unique, black-and-white art style (with individual panels drawn as if they were being pictured by a camera), a distinctive narrative that’s equal parts raving insanity and actual existential angst, a plethora of in-jokes and a loose fourth wall (Vasquez often comments on a particular panel, or scribbles notes regarding a scene) JtHM was in a genre all unto its own. The comic often featured “Meanwhiles,” aside stories that, apart from one, have no bearing to the plot; it was also interrupted by single-page, nonsensical Happy Noodle Boy comics featuring a stick figure shouting random obscenities, as well as the adventures of Wobbly-Headed Bob, an existential nihilist that would make Nietzche believe he was on happy pills.

The Front Cover of Johnny the Homicidal Maniac #1 © Wikimedia Commons

Plot-wise, the comic consisted of Johnny C., a serial killer, whom had to kill people mainly to paint a wall in his house with blood, because if he didn’t, something from “the other side” would get through. Of course, as per the title, Johnny was portrayed as an unstable, though extremely contemplative individual to whom the act of murder is basically like brushing his teeth. Case in point: a scene in the comic involves Johnny slaughtering an entire fast food place (going so far as to kill the cockroaches in the kitchen as well) because an elderly woman called him “wacky.” It branches out from there into details, such as how Johnny can keep killing people without getting caught, or the emergence of his “admirer.”

The comic’s main staple, however, was that Johnny served as ½ of a mouthpiece for Jhonen Vasquez in expressing open disdain towards those that would abuse others simply because they look different and are inclined to different things, mainly playing off on the jocks vs. Goths framework. The second half is a distributed mouthpiece that exists mostly in the supporting cast, and is used to express the same amount and kind of disdain for the excesses, self-indulgence and iniquitousness of the gothic subculture. The embodiment of his was Anne Gwish (read “anguish”,) an aside character inhabiting the same universe as Johnny, who was meant to be the epitome of the gothic stereotype. Smoking clove cigarettes, dressed entirely in black, a fan of “Pitchspade Symphony” (Switchblade Symphony that was considered a landmark in American gothic music, a point I plan to debate elsewhere) bitter, cynical, yet shallow and a bit too preoccupied with the shortcomings of other people around her, Anne Gwish is Jhonen Vasquez’s message: “I hate you all.”

Perhaps what’s emergent through these descriptions is that JtHM, perhaps unlike Serena Valentino’s GloomCookie (which itself existed inside, but separated the goods from the evils of the said subculture), strived to not only exist outside the gothic subculture, and even actively and clearly showed an opposition to it. Today, Johnny the Homicidal Maniac and it’s various merchandise can be found in every Hot Topic. The gothic subculture pretty much adopted the comic as its own (something Vasquez had prophesized by putting a “Johnny the Hamicidal Maniac” poster on Anne Gwish’s wall) and chose to make it one of the landmark masterpieces of gothic comics – the exact opposite of what it was meant to be.

Fillerbunny

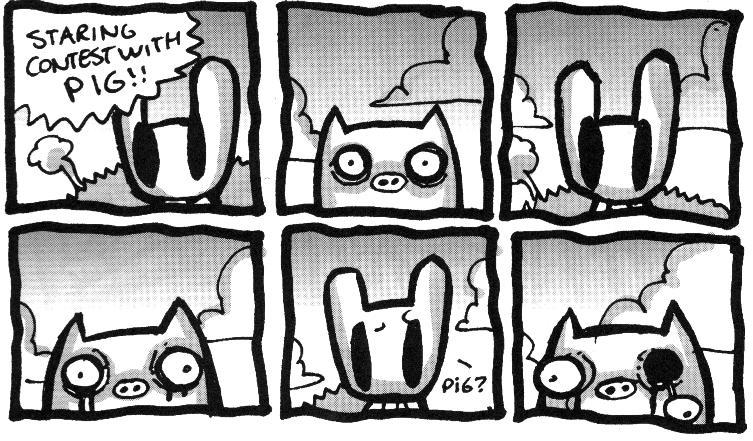

Fillerbunny was initially conceived as a cute bunny that inhabited single pages that would normally house adverts, therefore acting as “filler.” Jhonen Vasquez then saw fit to undertake an experiment and proceeded to write and illustrate 15 pages’ worth of material as he did all the other Fillerbunny pages: at the last possible second. Drawn in one night, the first Fillerbunny “book,” titled I Fill Up 15 Pages! Had the eponymous bunny at odds with an unseen, controlling force (presumed to be Vasquez, who appears in panels ranting about his inability to finish the book on time) that wants the bunny to entertain the readers. When the bunny declines, he (or she) is forced to do so, sometimes at gunpoint. It quickly becomes apparent that Fillerbunny only desires to die, for it cannot bear the weight of 15 consecutive pages.

Fillerbunny © webspace.webring.com

The book was, strangely, a success. It was just an experiment on par with the “Bad Art Collection” featuring inconsistent style (at one point devolving into mere scribbles,) zero continuity, little more than a bunny being subjected to strange methods of torture, and Jhonen Vasquez’s badly-drawn self-complaining about how his hand keept morphing into a “pickly-schlong thing.” Perhaps a rather extreme experiment, the book was wildly embraced by his readership, who seemed to harbor a belief that the work was nothing short of genius, when Vasquez himself was repeatedly quoted as saying it was just a book he draw in a single night with the intent to fill 15 pages, nothing further.

Invader Zim

Invader Zim (henceforth IZ) is perhaps the most misunderstood work by Jhonen Vasquez by far, as it was even misunderstood by its home studio, Nickolodeon. IZ is currently still a pop-culture phenomenon, a modern visual media Chernobyl that got misconstrued due to its high-tempo action and “Vasquezian” sense of humor.

To briefly comment: Zim is an Irken, an alien race that values universal conquest and snacks equally. Initially the reason why the firsts universal conquest operation failed, he forces his way into the assigning of tasks before the second attempt. Invaders’ work consist of blending in with their assigned planet, assessing its weaknesses and preparing it for invasion. Desperate to get rid of him, the Almighty Tallest (as height is rank in Irken society) give him a dysfunctional robot assistant (GIR, a scrapped unit put together on the spot) and send him off into space, hoping he will die on the way. Zim, however, accidentally makes it to planet Earth, settles in, and proceeds to gather information by attending school, where he meets Dib, a would-be paranormal investigator whom instantly recognizes him as an alien (Zim’s disguise being a wig and contact lens eyes doesn’t help.)

The show consisted mainly of Zim’s ill-thought out attempts to conquer Earth, Dib’s struggle to expose him as an alien and to stop his schemes, intercut with the raving insanity of GIR (Rosarik Rikki Simmons, the voice actor for GIR, once commented that he was being paid to spout nonsense in a studio,) coupled with top-notch animation, intriguing concepts and plots, numerous in-jokes and almost hyperactive pace made it an instant hit. I myself was initiated by my sister, also familiar with Vasquez’s work and it didn’t take long before our father was in the fold.

Invader Zim © Fanpop.com

Therein lies the first misconception on Nickolodeon’s part: although they had planned for IZ to be marketed to a slightly older than their 2-11 year-old demographic, they still accepted it to be watched mainly by teenagers to tweenagers. The problem with this was that IZ took its cues from science fiction, sci-fi and regular horror, alien invasion, cyberpunk genres of fiction and the aforementioned Vasquezian disdain for society in general. Scenes of torture and pain inflicted, mutations, open displays of parental neglect and the abuse of children through the school system were not exceptions: they were the rules.

Case-in-point: “Best Friend.” Zim, upon hearing comments that he is friendless and therefore “weird,” fears being exposed as an alien. Thus he holds an audition for three “friend candidates” consisting of an absorbency test (pressing their heads against spilt milk), an electrical conductivity test (basically giving them electricity through two conductor rods) and a final test (consisting of a toy car and a squirrel, unseen.) The chosen friend, Keef, quickly takes his “friendship” to stalker territory: he constantly walks around Zim’s house, turns up in it, refuses to leave Zim alone. Zim finds the solution in luring Keef into his house once again, whereby he plucks out Keef’s eyes and replaces them with hypnotic, cybernetic implants that will make Keef think the first thing he sees when opening them (a squirrel) is Zim, hence locking the desperate boy into an unending series of hallucinations whereby he chases squirrels all day, wondering why they won’t talk to him. And it’s played for laughs.

Invader Zim © roomwithamoose.com

As demonstrated, Nickolodeon’s error was not being able to anticipate how much older their “targeted older demographic” would be. The humor intercutting the nightmarish sequences and concepts that turn incredibly chilling when given a moment’s thought was simply there because Vasquez has always enjoyed random, almost spasmodic bursts of humor amidst even the most serious situation. As such, young adults and actual adults were the main demographic of IZ, leaving Nickolodeon’s hands largely empty where its core demographic was concerned – their misjudgment came from the fact that they did not anticipate just how far over the heads of their intended audience IZ would fly.

Unfortunately, theirs was not the only error. Recently (2012) Vasquez has gone on the record to say that IZ was being watched “wrong” as he frequently heard the audience giving pitying “awwws” to snippets of unmade episode scripts. He went on to say that he was shocked at the reaction, because the body of work was basically sci-fi horror, and nothing in it was intended to elicit that particular reaction. He has also, previously, expressed disdain towards the extreme amount of cuteness assigned to GIR, whom he portrays as a dangerously unstable robot armed to the teeth with various weapons (lasers, missiles, guns, etc.) who fails to grasp the implications of any action and is quite easily distracted. Further, GIR was subtly portrayed as harboring suicidal tendencies (expressing that he wanted to die at least twice), as well as (due to being put together from trash) experiencing hallucinations frequently: one instance of this had the cows he was looking at morph into sausages with top hats and canes, who chanted “Dance with us, GIR! Dance with us into oblivion!”

This misperception, after IZ’s cancellation, led to a phenomenon not unlike the above abstract – GIR’s perceived cuteness led to franchising focus almost exclusively on him, even though he was a supporting character. The culture of “cute” is an entirely different subject, one that was taken to its logical extreme in Japan decades ago, but the main perception remains globally that what is cute, is for children, and hence should be endorsed. This opened IZ to an audience closer in terms of age average to the one Nickolodeon originally intended, but by doing so, it shifted focus from elusive content to recognizable elements, therefore being made adoptable by hollowing out the larger scheme.

The Vasquezian Connection

The three examples given connect sublimely, as each one exemplifies a body of work that has an entirely different intent than the one the audience perceived, as well as the realm in which the body of work existed. Johnny the Homicidal Maniac wasn’t a goth comic, Fillerbunny wasn’t (and with its three books, still isn’t) a comic, period, and Invader Zim is not by any means children’s entertainment full of cute characters. In a way, these mark different Bela Lugosi’s Deads, their points being lost in the shuffle of growing attention to them. Of course, it must be mentioned that Jhonen Vasquez himself is an example to this phenomenon: going from an elusive, underground, inconoclastic cult figure to the accessible, almost chipper individual who has become the staples of various ‘cons. But individual devolution, in his case, is even more difficult and would warrant its own article.