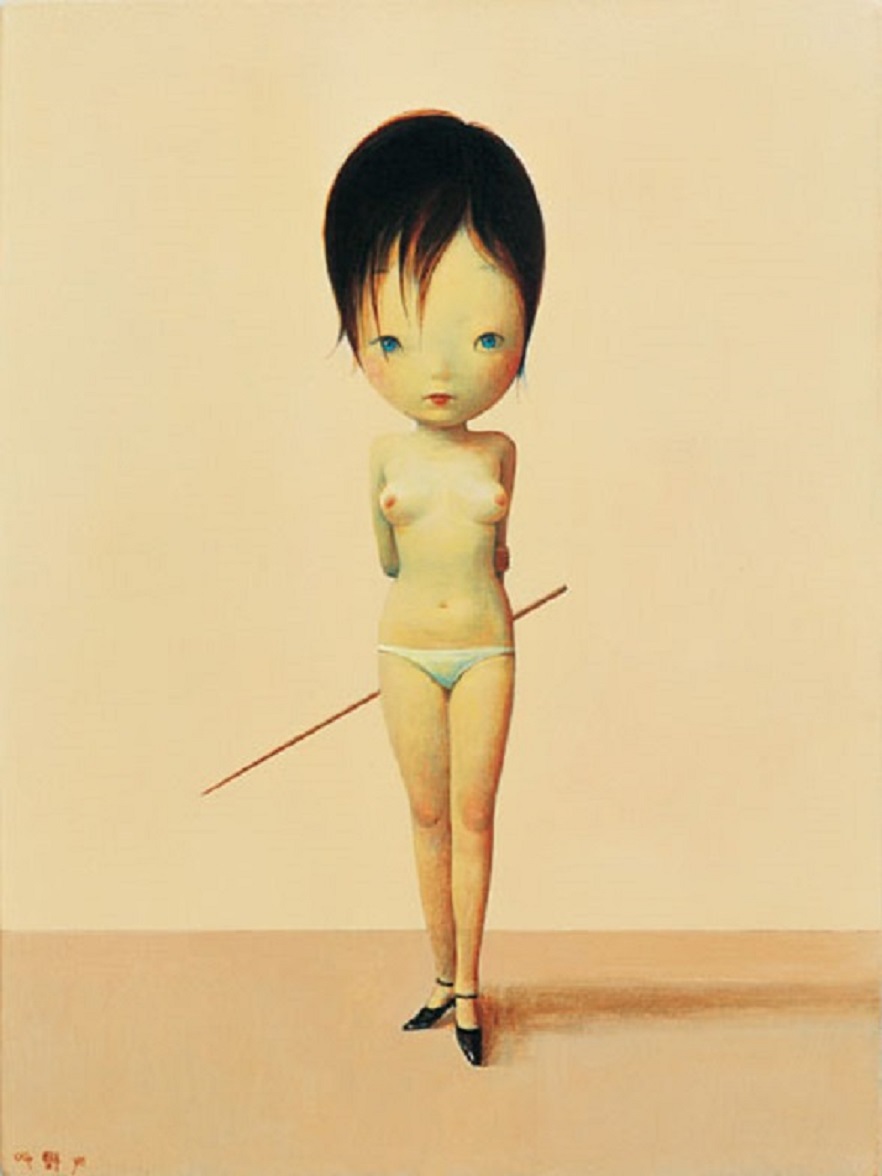

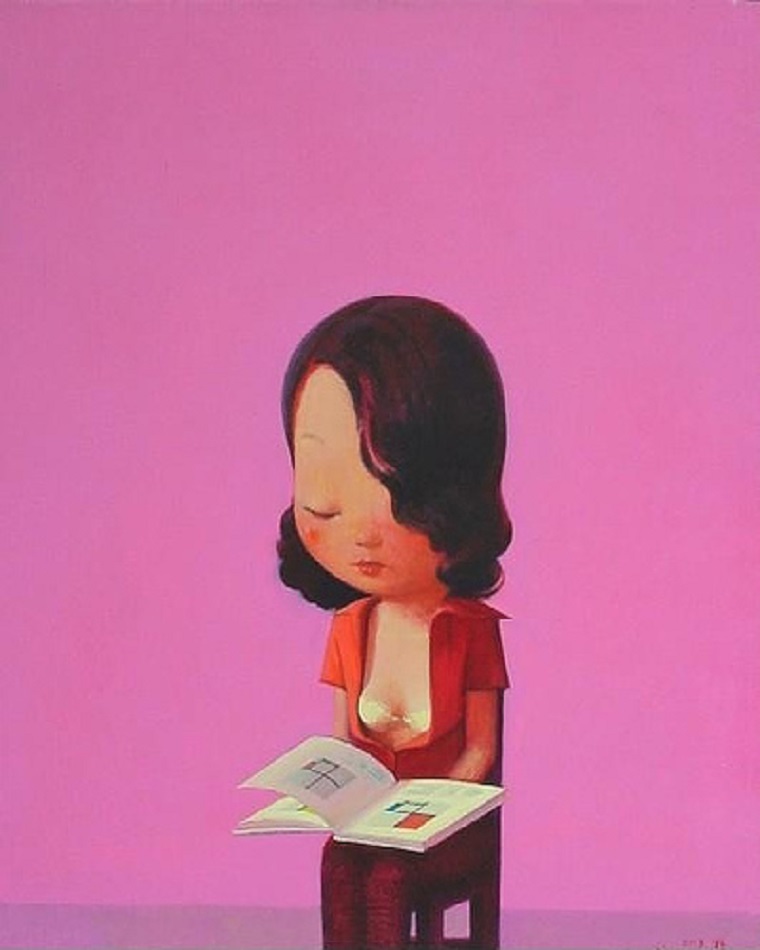

Girls with mischievous gaze look like from the cartoon, but they hold cigarettes in their hands, show their breasts or sadly hold pink pig near their chests and vivid colors surround everything. Here’s what Liu Ye is, artist who seeks for beauty and concentration in human feelings, hope and wild emotions in his works.

Painter Liu Ye was born in China in 1964. He is a part of a generation of artists that grew up during the Cultural Revolution and were visually affected by the kitsch aesthetic of propagandistic art. His political and cultural background led him to create seemingly childlike or naïve worlds full of fantasies and fairy tales; however, Ye contrasts his lighthearted style with imagery alluding to the global catastrophes.

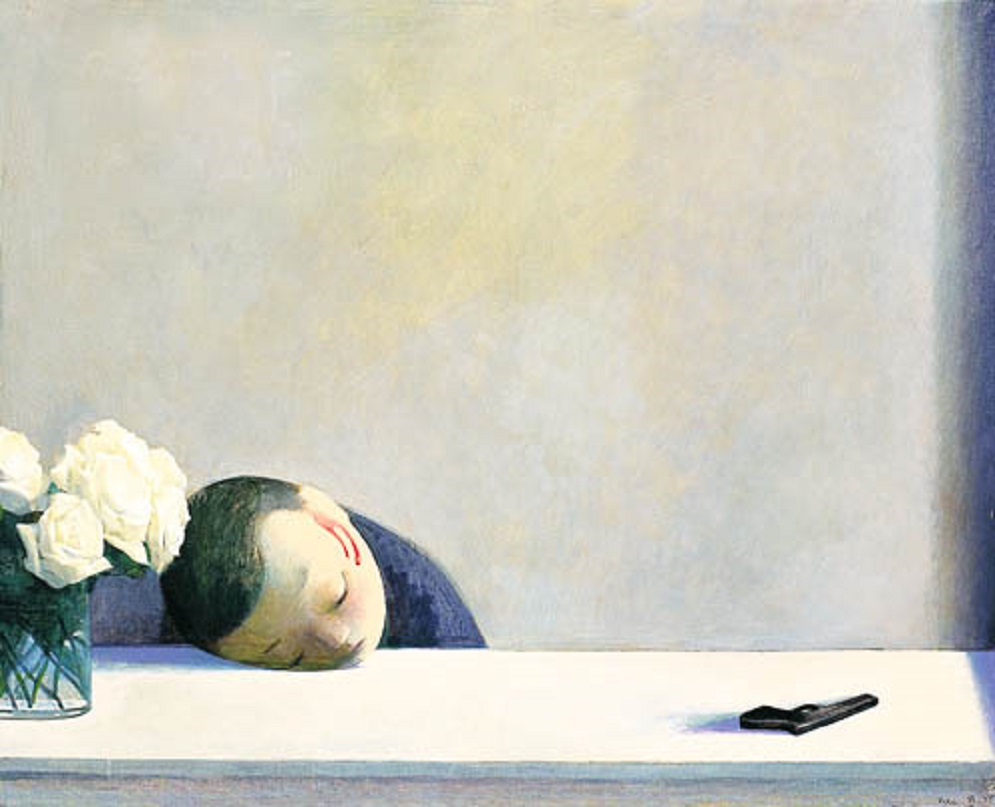

In Liu Ye’s art, humor and sadness blend into a whole. The stillness of his ironic images provides us with a deep sense of detachment and timeless freedom. Part of the post 89′ avant garde movement, his art is disinterested in the external flux taking place in modern China. Instead, Liu captures the inner solitude and vulnerability of the artist in the face of the enormous changes taking place on a global scale and in the Chinese society.

© soko-barefoot.blogspot.com

After studying at the School of Arts and Crafts and the Central Academy of Fine Arts in his hometown Beijing between 1984 and 1989, Ye received a degree from University of Fine Arts in Berlin in 1994.

Liu Ye is best-known for his colorful cartoon like characters in playful, naughty adolescent scenes. Influenced by Mondrian and abstract art, Liu Ye uses the color schemes and patterns of a Mondrian – and even images from Mondrian’s works – and sets them in China, with young girls, bearing a breast, smoking, acting childlike or closing their eyes to enter a dreamlike state. Unlike many contemporary artists he has steered away from politics and chosen to focus on human emotions and childlike images.

© soko-barefoot.blogspot.com

As the art historian Pi Li says, “The major difference between him and his contemporaries was that he did not go through the period of rage around 1989, nor did his works contain elements of ‘collective’ images.” Around the same period of time, Liu Ye was witnessing the change in Europe as the Berlin Wall came down, touring Europe’s art museums and studying masters of Western modernism like Paul Klee and Johannes Vermeer. Instead of focusing on his Chinese origin, Liu Ye embraces some more universal themes like beauty, feeling and hope in his works. As he puts it, ” Seeking beauty is the last chance for human beings. It is like shooting at the goal; it arouses an emotion that is wild with joy.”

© soko-barefoot.blogspot.com

By the time Liu Ye went back toChina in 1994, his works were deeply influenced by German Expressionism, showing intense personal expression with an overall gloomy tone. In that period, he started to portray himself more as a little boy than a young man as he did before. More female figures appeared. The settings of his painting moved from rooms to theatres where scenes he saw inChina as a little boy, his childhood dream were depicted. Chorus, fleet and sailor boys were repetitive subjects portrayed during the period. His preference for using primary colors can be traced to his childhood days inBeijing as well. “I grew up in a world of red,” he recalls, “the red sun, red flags, red scarves with green pines and sunflowers often supporting the red symbols.“

© soko-barefoot.blogspot.com

Today, one of China’s best-selling contemporary artists, Liu Ye is a striking example of a Chinese artist exploring his own internal world through external and anonymous figures and western icons. Most of his work is done in bright, vivid and warm colors while the more melancholic ones are toned down to dark and cold blues.

© soko-barefoot.blogspot.com

A painting by Liu Ye sold for $ 2.5 million at a Hong Kong auction in 2010. It was the most for a Chinese contemporary artist in few years by then.

Liu’s acrylic-and-oil “Bright Road,” showing a smiling couple with a flaming jet in the background, fetched an artist record. It was one of seven Chinese contemporary works that made $1 million or more at Sotheby’s sale.