Victor Marie Hugo, the famous French poet, novelist and playwright, born on 26 February 1802 in Besançon, France, left an indelible mark not only on the world of literature, but also on the world of social activity. Hugo was not only a literary genius but also a fierce advocate of social justice, whose ideas challenged the status quo – the social and political situation of the time – and pushed for social transformation. Even after his death in 1885, the writer’s life, work and ideas continue to fascinate and inspire generations of readers.

Hugo’s life was marked by a wide range of personal and political circumstances that had a profound impact on his future as a writer and activist. Victor was the third son of Joseph-Léopold-Sigisbert Hugo (1774-1828), who served in Napoleon’s army, and Sophie Françoise Trébuchet (1772-1821), an artist who espoused royalist ideas, which were later taken up by Victor himself. Hugo’s upbringing was strongly influenced by the political climate of the time. His childhood was marked by his father’s constant travels with the imperial army and his parents’ frequent disagreements and differences of opinion, which led to their subsequent separation. It was a chaotic and volatile time in Victor’s life, with frequent moves to different parts of Europe. For example, in 1811, when he was nine years old, the whole family moved for a year to Madrid in Spain, where his father had gone to serve. It was at this time that Hugo’s love of literature and writing began to grow, and he immersed himself in the work of Spanish playwrights and poets, which fuelled his own creative aspirations. In 1812, Hugo’s parents went their separate ways, with Victor returning to Paris to live with his brother and mother.

Between 1815 and 1819, Hugo, together with his brother Eugène, attended a boarding school in Paris, later the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, at their father’s request. Victor did well in his studies, and after school he and his brother continued their studies at the Faculty of Law in Paris, but he always had other ambitions: while still a student, Victor filled his notes with his own poems and translations of texts by other authors such as Virgil. Encouraged by their mother, the Hugo brothers started the Conservateur Littéraire (1819-1821), which was distinguished by Victor’s own articles and texts, as well as reviews.

Hugo’s mother died in 1821, and a year later his brother Eugène was institutionalized for mental health reasons. In the same year, at the age of 19, Victor married his childhood friend and crush Adèle Foucher and published his first book of poetry, Odes et poésies diverses (Odes and other poems), the royalist sentiments of which earned him a pension from the French King Louis XVIII. Victor and Adèle had a total of five children between 1823 and 1830: Léopold (who died at the age of three months), Léopoldine, Charles, François-Victor and Adèle. 25 February 1830. On 25 February, the first production of Hernani, based on his romantic play, was staged at La Comédie Française (theatre in Paris), breaking down the rules of classical theatre and establishing Hugo as the leader of the French Romantic movement.

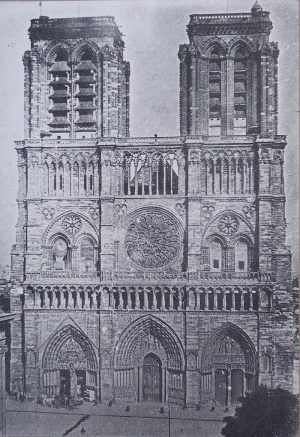

One of his most important and best-known works, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame de Paris, published in 1831, immediately attracted great interest and acclaim. Begun in 1829, the work became a kind of tool to save the cathedral of Paris from a rather sad fate. After the French Revolution, many Gothic buildings and monuments, including the Paris Cathedral, had fallen into severe disrepair, and the author was worried that they were falling into disrepair and neglect. He wanted to write a novel that would portray the cathedral as a sacred work of art, as well as denounce the public’s indifference to the building’s condition, and help to encourage its preservation. More than 150 years ago, it was this immortal work that inspired the French to rise up and preserve this historic cathedral, without which the Paris of today is simply unimaginable.

In addition to The Paris Cathedral, between 1830 and 1848 Victor Hugo published four books of poetry, one novel, and seven plays, several of which, including The King’s fool, were censored for their criticism of the French monarchy. Those years were also marked by twists and turns in his personal life that changed both his life and his artistic path. In 1833, he met the actress Juliette Drouet, who soon became his mistress, and together with his wife Adèle, the other great love of his life. Of course, the greatest and most decisive blow was the drowning of his beloved Léopoldine, his nineteen-year-old daughter, in the River Seine in 1843, after whose death he began to write less and to concentrate more on politics. He supported and backed the monarchy and was appointed by the then King Louis-Philippe as one of the highest-ranking members of the nobility of France under the Peer system of the Peerage, which was still in force at the time (members of the nobility of this title could, with the permission of the King, sit in the upper chamber of parliament (the Peerage)). Victor Hugo Peer held the title and sat on the conservative political side in the House of Peers from 1843 until 1848, when the system was abolished.

The overthrow of King Louis Philippe’s monarchy in 1848, with the granting of the franchise to the population, abolished the Persian system, and thus the rank and political power of the Hugo upper class. After some time to reflect on his future plans, Victor began to support a second French republic, and was elected to the Constituent Assembly in June 1848, and then to the National Assembly (the lower house of Parliament) in May 1849. During these years, Hugo made some of his most famous speeches while sitting with Parliament: on 11 September 1848 on freedom of the press (“Freedom of the press, together with universal suffrage, is the thought of all, which enlightens the government of all.”), on 15 September 1848 on freedom of the press. 9 July 1849 on poverty (“I am not one of those who imagine that you can abolish the sufferings of this world; suffering is a divine law; but I believe and declare that you can abolish poverty.”)

The Revolution of 1848 and the barricades in the city streets inspired the scenes of street fighting in another of Hugo’s well-known novels, Les Misérables, although the novel itself is set during the earlier uprisings of 1832. Published in 1862, the book became rapidly popular because of the ideas it managed to contain and because of its sharp criticism of the problems of 19th century France. Women’s rights, conflicts between different generations, the cruelty of the justice system and the incompetence of the institutions of society are all universal problems that have appeared in one form or another in every century, and so the book is still popular and relevant today.

On 2 December 1851, the French President Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon I, staged a coup d’état and restored the imperial regime under the name of Emperor Napoleon III. Victor Hugo, who actively opposed the coup himself and encouraged others to do so, was threatened with arrest and left Paris for a temporary refuge in Brussels. Exiled from France, Hugo and his family went into exile on the island of Jersey for 19 years, and later on the island of Guernsey (an island off the coast of France, belonging to the British Crown but not part of the United Kingdom or Europe), refusing the amnesty (full or partial pardon) guaranteed by Napoleon III in 1859.

A satirical book of poems, published in 1853 and entitled The Empire in the Pillory, criticising the Second Empire, circulated secretly on the streets of France. It was during his exile that Hugo plunged back into writing. His poetry collection Contemplations, published in 1856, in which he poured out all the grief he felt at the loss of his beloved daughter, helped him to acquire the legendary Hauteville house overlooking the sea on the Isle of Guernsey, where he wrote some of the most important works of his life, the novels Les Misérables (1862), Toilers of the Sea (1866), The Man Who Laughs (1869), an essay on William Shakespeare (1864), a collection of poetry, The Songs of the Streets and Woods (1865), and an epic, The Legend of the Ages (1859)

Like many of his novels, The Man Who Laughs contains very important political and social ideas, a kind of Hugo-like struggle for humanity and the rights of all people under the rule of a senseless aristocracy, which inspired the Joker in Batman comics and pop culture. One of the main themes of this novel is the exploration of social injustice and inequality. The book delves into the stark class distinctions and social norms of the time, which encouraged cruelty and rejection of the most vulnerable members of society. In the novel, Hugo masterfully and clearly depicts the harsh reality faced by the poor and the marginalised at the time, highlighting the suffering and struggles they endured to get by. Another important theme of the novel is love and the power of acceptance in the face of social rejection. It criticises the ruling elite, sheds light on the prevailing corruption and moral decay among those in power, and emphasises the importance of justice and an impartial society. “The Man Who Laughs and the novel’s protagonist, disfigured by a cruel smile on his face – a metaphor for the masks people wear and society’s expectations – explore the complex nature of identity, appearance and society’s often superficial assessments.

Hugo’s wife Adèle died in 1868. About two years later, in 1870, the day after Napoleon III’s surrender, Hugo returned to Paris to the applause of the public. In 1871, while the city was devastated by a revolt and an attempt to establish a new government (including the historic Bloody Week, which claimed more than 20,000 lives), Hugo went to Brussels to deal with the death of his son Charles. However, while in Belgium, he took in and gave refuge to some of the rebels who had fled Paris, leading to his expulsion from Belgium and a few months in Luxembourg. In 1872, Victor’s daughter Adèle was admitted to a psychiatric hospital and a year later he lost his son François. Marked by painful losses and blows, two years later he published his last novel, The Ninety-Third Year (Quatrevingt-treize), and his political texts and speeches from 1841 to 1876 appeared the following year in Actes et Paroles (Deeds and Words collection). In 1876, he was elected to the Senate of France, which was the height of his political and creative fame. Encouraged by his love for his two grandchildren, Hugo also wrote a book of poetry, L’Art d’être grand-père (The Art of Being a Grandfather), which was published in 1877, after his death. He died on 22 May 1885 and his funeral was attended by some 2 million people at the Panthéon in Paris.

Victor Hugo’s life was marked by painful losses, political unrest, exile, great literary talent and political ideologies. All that he lived through and experienced from an early age helped to shape him as a compassionate and socially responsible writer, who later became a literary titan of sorts, a champion of social justice, a radical and outspoken political writer who lent his voice and support to movements around the world, and who helped to change the world.